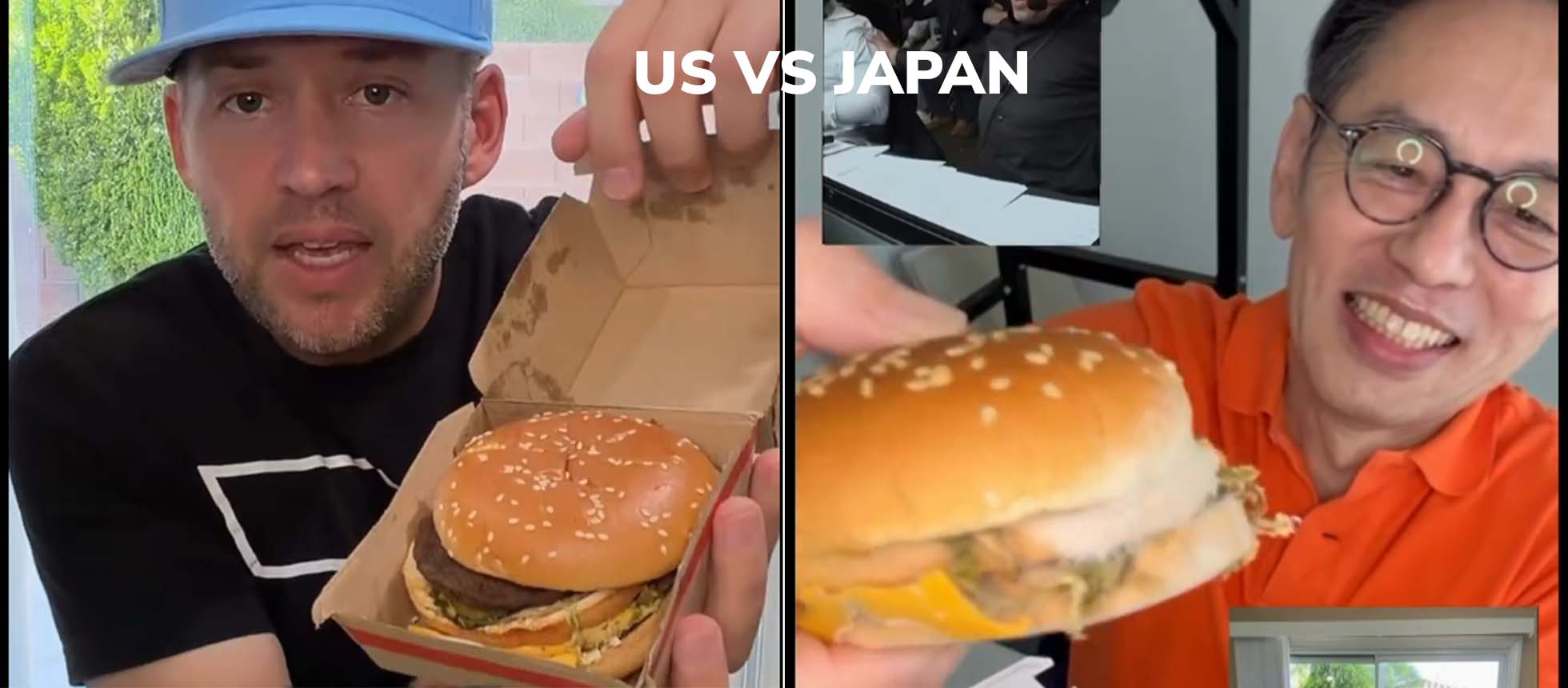

When a McDonald’s Big Mac sits untouched for ten months and emerges looking virtually identical to the day it was purchased, most would call it unsettling. When that same burger, purchased 5,000 miles away in Japan, transforms into a moldy specimen within 30 days, it raises an uncomfortable question about what Americans are actually eating.

A recent viral experiment comparing American and Japanese Big Macs has exposed a stark reality: the same menu item from the same global corporation behaves dramatically differently depending on which side of the Pacific Ocean you’re eating it. While the Japanese version decomposed as real food should, its American counterpart remained eerily preserved, defying the natural process of decay that governs organic matter.

“These are the same burgers,” noted the experimenter in a video documenting the 30-day comparison. “Why does Japan’s look like Hagrid, and mine looks like it got Botox?”

The implications extend far beyond a single fast-food chain. This discrepancy points to fundamental differences in food regulations, ingredient standards and corporate practices that make the same branded product substantively different based on geography.

The American Big Mac’s resistance to decomposition isn’t a testament to superior food science—it’s a red flag about what’s actually in the product. Food preservation at this level requires a mix of additives, preservatives and processing methods that extend shelf life but raise serious questions about biological impact.

Longevity expert Bryan Johnson has spent considerable time analyzing what he calls the “hidden truth” behind McDonald’s most popular items. His investigations reveal that the company’s transparency claims often exploit regulatory loopholes. Take their world-famous fries, for instance. While packaging proudly displays “zero grams of trans fat,” Johnson explains this exploits an FDA provision:

“That does not mean it’s without trans fat. It means the FDA says that you can be under .5g and list zero.”

The fries present additional concerns beyond misleading labels. Fried in refined seed oils that oxidize under high heat, they form aldehydes—compounds that damage proteins, cell membranes and DNA. The process creates what Johnson identifies as “accelerated pathways to heart disease, liver disease, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.”

Perhaps most alarming is the acrylamide content. When starch encounters high frying temperatures, it produces these harmful compounds. Johnson’s analysis found McDonald’s fries contain

“20 times higher”

acrylamide levels than a homemade baked potato.

“Every time you eat these fries, you’re essentially fast-forwarding your biological clock,”

he explains.

The Big Mac itself presents a masterclass in engineered consumption. Despite its wholesome marketing image, the sandwich delivers nearly half your daily sodium allowance and packs 9 grams of added sugar—comparable to a glazed donut. This sugar content serves a deliberate purpose: triggering an insulin spike that creates temporary euphoria followed by a crash approximately 90 minutes later, leaving consumers hungrier than before and primed for another purchase.

Johnson doesn’t mince words about the burger’s overall impact:

“It’s a destruction machine.”

The industrial beef comes from grain-fed cattle producing meat with compromised omega fatty acid ratios while emulsifying agents disrupt gut health. The combination creates what he terms

“a perfect storm of metabolic dysfunction.”

Yet in Japan, where stricter food regulations and different sourcing standards apply, that same Big Mac contains fewer preservatives and additives—allowing it to decompose like actual food.

Among Johnson’s most disturbing findings involves chicken McNuggets and their aluminum content. Sodium aluminum phosphate, used as a leavening agent, exposes consumers to concerning levels of this neurotoxic metal. A 20-piece box delivers 2.8mg of aluminum—28 times higher than levels linked to cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s risk in French population studies.

The nuggets also contain TBHQ (tertiary-butylhydroquinone), a petroleum-derived preservative. Laboratory studies showed cell damage, DNA alteration and increased tumor growth in animal subjects exposed to this compound, yet it remains in products marketed to children.

McDonald’s beverage lineup represents what Johnson calls

“liquid destruction.”

The caramel frappé tops his concern list with 70 grams of added sugar per serving. Swedish longitudinal studies showed that even a 5% increase in added sugar intake correlated with a 23% spike in all-cause mortality rates.

The frappé’s caramel coloring contains 4-methylimidazole, which produced lung tumors in laboratory mice. While regulatory agencies claim safe consumption levels exist, Johnson argues that no carcinogen exposure can be truly safe when consumed regularly by millions.

The recent viral photograph of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. holding a McDonald’s Big Mac aboard a private jet—while promoting a “Make America Healthy Again” agenda—crystallized a troubling contradiction. Kennedy, appointed to a health leadership position despite years of criticizing processed foods, found himself literally consuming the products he’s warned against.

In a podcast appearance, Kennedy described the limited food options on that same aircraft as

“poison,”

noting passengers face a choice between

“KFC or Big Macs”

with everything else being

“inedible.”

Yet the photograph captured him smiling while holding exactly what he’d identified as harmful.

“We’re watching the commodification of health advice in real time,”

Johnson observes.

“These influencers build audiences by promoting wellness then sell those same audiences back to the food companies making them sick.”

Johnson’s research reveals that McDonald’s success stems from deliberate food engineering designed to create dependency. The combination of sugar, salt and fat triggers dopamine release patterns while subsequent crashes generate cravings. This biochemical manipulation, supported by marketing associating McDonald’s with positive emotions and childhood memories, creates a cycle difficult to break.

“McDonald’s doesn’t sell food. They sell dependency wrapped in nostalgia and convenience,”

Johnson explains.

“Every product is designed to ensure you’ll need another one.”

Beyond obvious concerns like obesity, these foods systematically damage the gut microbiome—bacteria regulating immune function, neurotransmitter production and overall health. Emulsifiers, preservatives and artificial compounds create what Johnson calls

“leaky gut syndrome,”

allowing toxins into the bloodstream and triggering systemic inflammation.

This microbiome disruption may contribute to rising rates of autoimmune diseases, depression, anxiety and cognitive decline—conditions that appear unrelated to diet but stem from ultra-processed food consumption.

McDonald’s international reach means American food engineering gets exported worldwide, creating global epidemics of obesity, diabetes and chronic disease. Countries adopting Western fast-food diets experience rapid increases in previously rare conditions, demonstrating the causal relationship between ultra-processed foods and population decline in public health.

Yet the Japanese Big Mac experiment proves these health consequences aren’t inevitable. When regulations demand higher standards and restrict harmful additives, even fast food behaves differently—decomposing naturally rather than remaining preserved indefinitely.

The contrast between moldy Japanese Big Macs and eerily preserved American ones isn’t just a curiosity—it’s evidence of systemic differences in how food is regulated, produced and sold. While both versions remain ultra-processed and nutritionally questionable, the American variant’s resistance to natural decay reveals an additional layer of concern about what preservatives and additives are considered acceptable.

“The question isn’t whether McDonald’s will change,”

Johnson concludes.

“It’s whether Americans will finally demand better than convenient poison wrapped in clever marketing.”

As the experimenter in the viral video suggested, perhaps you could get a Big Mac that actually molds by booking a flight to Tokyo. Or perhaps the real lesson is questioning why American consumers should accept food that defies the basic biological process of decomposition and what that acceptance says about the state of the nation’s food system.

The evidence sits preserved after ten months, looking disturbingly fresh. The choice of what to do with that information remains with those still consuming it.