Privacy advocates are raising alarms over Microsoft‘s controversial new limitation on a face-recognition feature being tested in OneDrive, the company’s cloud storage service. Users who wish to disable AI-powered facial scanning of their photos can only do so three times per year. This restriction has privacy experts questioning whether users truly have control over their personal data.

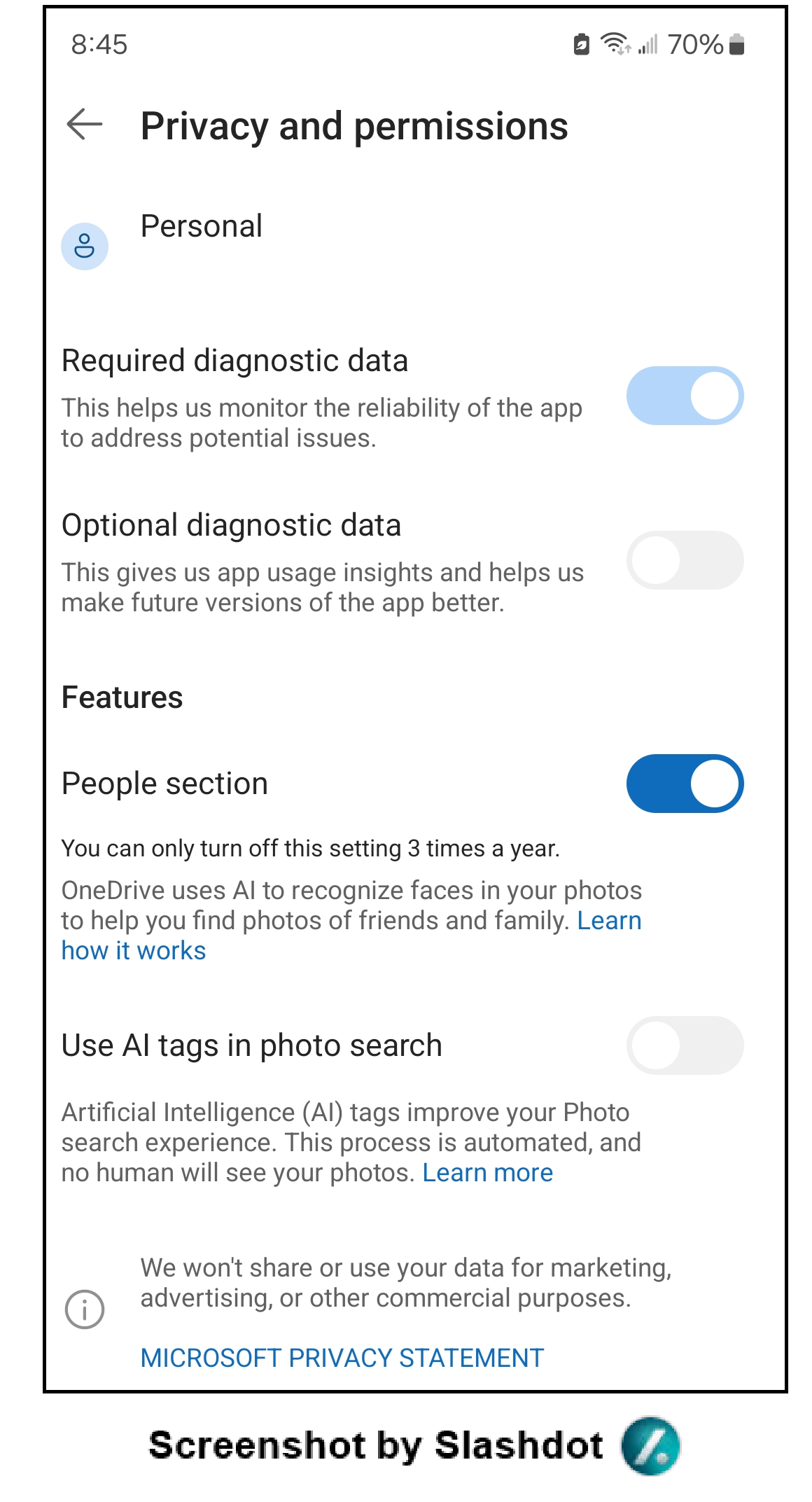

The issue came to light when a OneDrive user attempted to disable the facial recognition feature after uploading a photo through the mobile app. Upon navigating to Privacy and Permissions, they encountered an unexpected message: “OneDrive uses AI to recognize faces in your photos…” followed by a startling caveat—”You can only turn off this setting 3 times a year.”

When the user attempted to move the slider to “No,” it snapped back to the enabled position with an error message stating “Something went wrong while updating this setting.”

Microsoft confirmed to Slashdot that the feature is currently being rolled out to a limited number of users as part of a preview program. However, the situation surrounding the feature remains murky. A link to Microsoft’s privacy statement leads to a support page claiming “This feature is coming soon and is yet to be released,” with a message that has been displaying “Stay tuned for more updates” for nearly two years.

When asked directly about the three-times-per-year limitation, Microsoft’s representative declined to provide an explanation. The company also avoided answering whether users could toggle the setting at any time they chose, or if the three opportunities were restricted to specific dates.

Regarding the technical issue preventing users from selecting “No,” Microsoft’s response focused on troubleshooting rather than addressing the broader policy concern. The representative asked for device information to investigate the problem but offered no clarity on whether this was an isolated glitch or a systematic issue.

On the question of whether OneDrive has already been using facial recognition technology on user photos, Microsoft provided only a boilerplate response about privacy being “built into all Microsoft OneDrive experiences” and referenced compliance with various regulations including GDPR and the Microsoft EU Data Boundary.

Perhaps most significantly, Microsoft was asked why it chose to make facial recognition an opt-out feature rather than opt-in, a approach generally preferred by privacy advocates. The company’s answer was vague at best, stating that “Microsoft OneDrive inherits privacy features and settings from Microsoft 365 and SharePoint, where applicable.”

This response does little to address the fundamental concern: users are being automatically enrolled in facial scanning unless they take action to prevent it—and even then, their ability to reverse that decision is severely limited.

Thorin Klosowski, a security and privacy activist with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, expressed serious concerns about Microsoft’s approach. “Any feature related to privacy really should be opt-in and companies should provide clear documentation so its users can understand the risks and benefits to make that choice for themselves,” Klosowski said.

He was equally troubled by the three-times-per-year restriction. “People should also be able to change those settings at-will whenever possible because we all encounter circumstances were we need to re-evaluate and possibly change our privacy settings.”

The implications extend beyond a single feature. Microsoft’s decision to limit how often users can disable facial recognition raises questions about who truly controls personal data stored in cloud services. If a company can dictate not only the default settings but also how frequently users can change those settings, the concept of user consent becomes increasingly hollow.

For individuals concerned about biometric data collection, the situation is particularly troubling. Facial recognition technology creates unique identifiers from photographs that can be used to track individuals across images and potentially link data in ways users never anticipated or approved.

The fact that some users are experiencing errors when attempting to disable the feature adds to the concern. Whether these technical issues are bugs or features remains unclear, but the effect is the same: users who want to protect their privacy find themselves unable to do so.

As Microsoft continues its preview rollout, the company has provided no timeline for when the feature might become widely available or whether the three-times-per-year limitation will remain in the final version. For now, users caught in the preview program appear to have limited recourse if they object to having their photos scanned for faces. This is a situation that privacy advocates argue should never have been allowed in the first place.