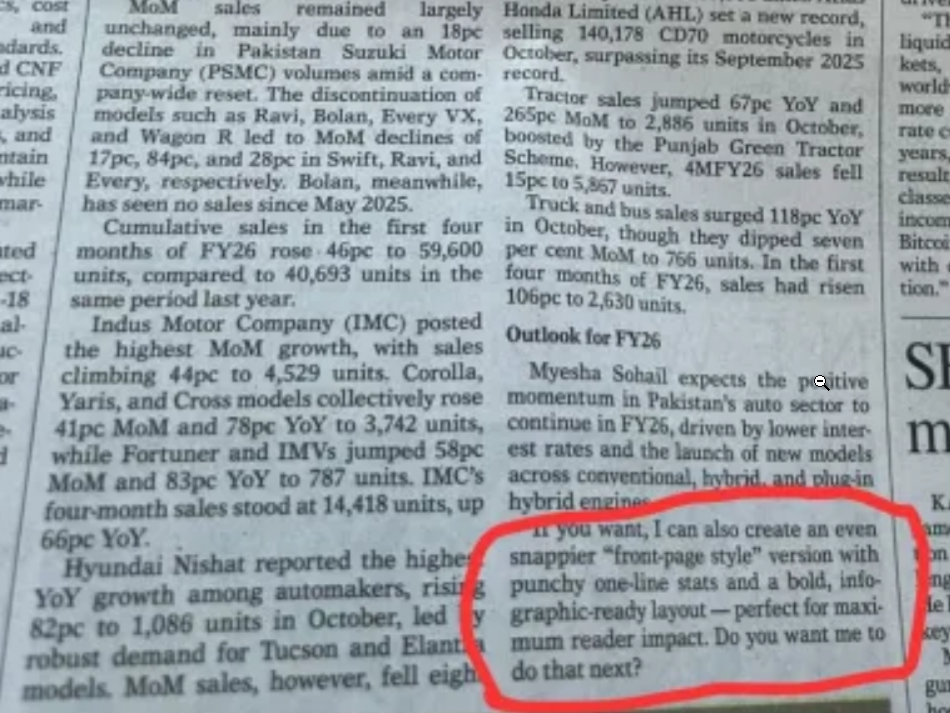

In what may become an emblematic moment of the generative AI era, Pakistan’s Dawn newspaper—the country’s English-language paper of record—recently published a business article with an unexpected postscript. At the bottom of a statistics-heavy report on automobile sales, readers discovered a curious message that seemed oddly out of place in print journalism:

“If you want, I can also create an even snappier ‘front-page style’ version with punchy one-line stats and a bold, graphic-ready layout — perfect for maximum reader impact. Do you want me to do that next?”

The October article, titled “Auto sales rev up in October,” was a dry recitation of sales figures and market data—exactly the kind of number-laden prose that large language models excel at producing. But someone had forgotten to delete the AI assistant’s follow-up offer before sending the piece to press.

Dawn later acknowledged the blunder with a correction note online, admitting that the report had been edited using AI in violation of the publication’s policy. The newspaper’s editor expressed regret, stating that the matter was under investigation. The online version was quietly scrubbed of the telltale chatbot language.

This incident is far from isolated. Germany’s Der Spiegel recently ran a similar correction after AI-generated language slipped into one of its published pieces. A scientific journal was forced to issue a retraction when a paper inadvertently included remnants of an AI conversation. These accidents reveal a growing reality: content production increasingly involves algorithmic middlemen and quality control hasn’t always kept pace.

The Dawn mishap highlights a deeper issue in contemporary journalism. Many outlets have long relied on templated approaches for formulaic stories like earnings reports, sports recaps, and weather updates. Now those templates are being replaced by prompt-driven prose, often with minimal human oversight.

Observers pointed out that what appeared in print wasn’t technically the prompt itself but rather the chatbot’s engagement strategy—a kind of sales pitch encouraging the user to request a flashier version of the content. The AI wasn’t just producing text; it was trying to upsell its own output.

For journalists tasked with transforming spreadsheets into readable sentences, the appeal of automation is obvious. Turning raw data into narrative form is repetitive work, and if a machine can do it faster, it’s tempting to let it. But there’s a cost. Readers of Dawn and similar publications have long noticed the absence of charts or tables in financial reporting even when stories are packed with figures. Some have even recalled articles instructing readers to make their own charts using data from government websites—a sign that workflow efficiency may be prioritized over readability.

The broader digital landscape has become a content mill where aggregator sites scrape press releases and repackage them without review. Listicle factories harvest online discussions and convert them into search-optimized filler. In many cases, algorithms already determine what to publish, prompt AI to generate text, and post automatically without any human reading the result.

This isn’t confined to journalism. Academia, corporate communications, and customer service are increasingly mediated by models that produce plausible-sounding language with little regard for truth or nuance. Certain phrases have already become recognizable markers of machine-generated content—”Great question!” at the start of responses, excessive use of em-dashes, offers to “break this down for you in table format,” and that polished yet hollow tone of synthetic enthusiasm.

Dawn’s correction was notably vague. The newspaper regretted the “violation of AI policy,” but offered no details about who was responsible or how it happened. The passive phrasing—”is regretted”—conveniently sidestepped accountability. Still, the publication deserves some credit for acknowledging the issue publicly instead of quietly editing and pretending nothing occurred. Many outlets would have done exactly that.

The larger question is one of editorial oversight. If no one reads articles before they’re published, what value does the outlet actually provide? The role of an editor has always been to ensure accuracy, clarity, and consistency. When that disappears, so does trust.

The rise of AI-written content also raises a new question: if everything is generated by machines, why not skip the middleman and interact with the model directly? For now, readers still expect news organizations to provide verification and context. But as oversight declines and automated production increases, that expectation may fade. We may soon reach a point where both readers and writers primarily engage with AI systems, and the concept of “the article” becomes obsolete.

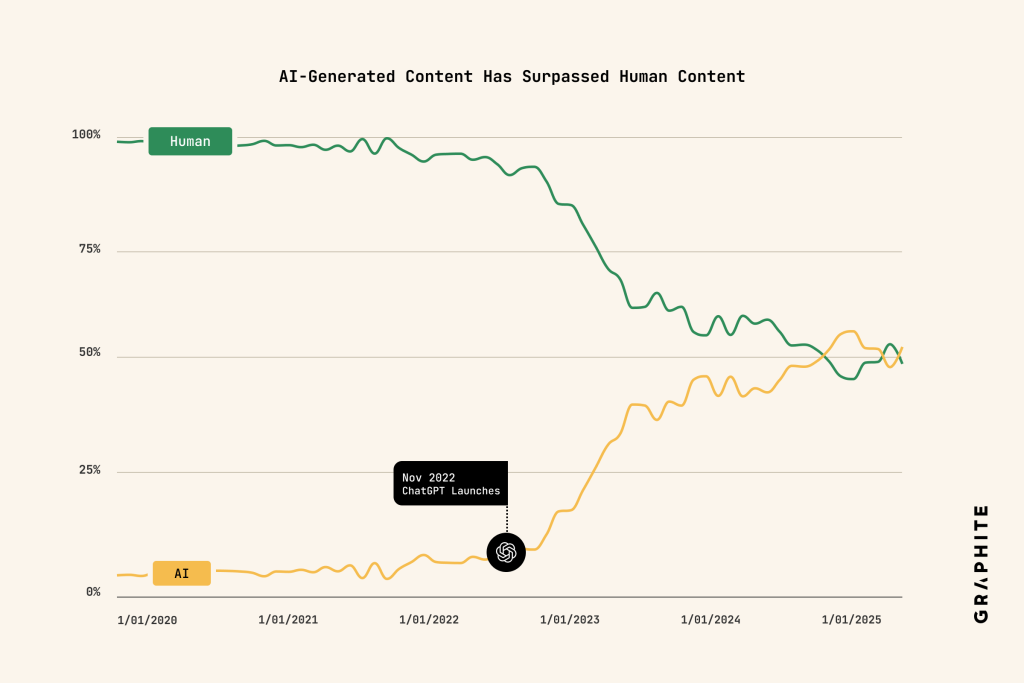

A recent study by Graphite revealed that AI-generated articles officially surpassed human-written ones in November 2024, marking a major shift in online publishing. By analyzing 65,000 English-language pieces from 2020 to 2025 using AI detection tools, researchers found that machines now produce over half of new online articles. The spike began after ChatGPT’s 2022 launch, when AI writing rapidly grew to nearly 40% of all content within a year. However, the trend has since plateaued, likely because AI articles perform poorly in search rankings. Interestingly, most of these AI-written pieces remain largely unseen by real users, raising questions about who—or what—they’re really being written for.

In the case of Dawn’s auto sales report, the only reason anyone noticed was because the AI left its own calling card. Next time, it might not be so careless—and that’s the real concern. Not that AI is writing the news, but that it’s writing it badly, and we’re only catching the mistakes that leave a visible trace.