A leading international organization dedicated to cryptography research has been forced to void its recent election after discovering that one of three secret keys needed to decrypt the voting results has gone missing — a scenario that would seem almost satirically improbable for a group whose entire expertise centers on securing information.

The International Association of Cryptologic Research, based in Bellevue, Washington, made the embarrassing announcement last Friday. The organization, which represents thousands of cryptography researchers worldwide and publishes some of the field’s most influential work, had conducted elections for three director positions and four officer roles using an ultra-secure digital voting system called Helios.

The problem? The system required all three trustees to provide their individual cryptographic keys to unlock the results. When one trustee couldn’t produce their key, the encrypted vote tally became permanently inaccessible.

“Regrettably, we have encountered a fatal technical problem that prevents us from concluding the election and accessing the final tally,” the organization stated in its announcement. “We are deeply sorry for this failure and for the disruption it has caused.”

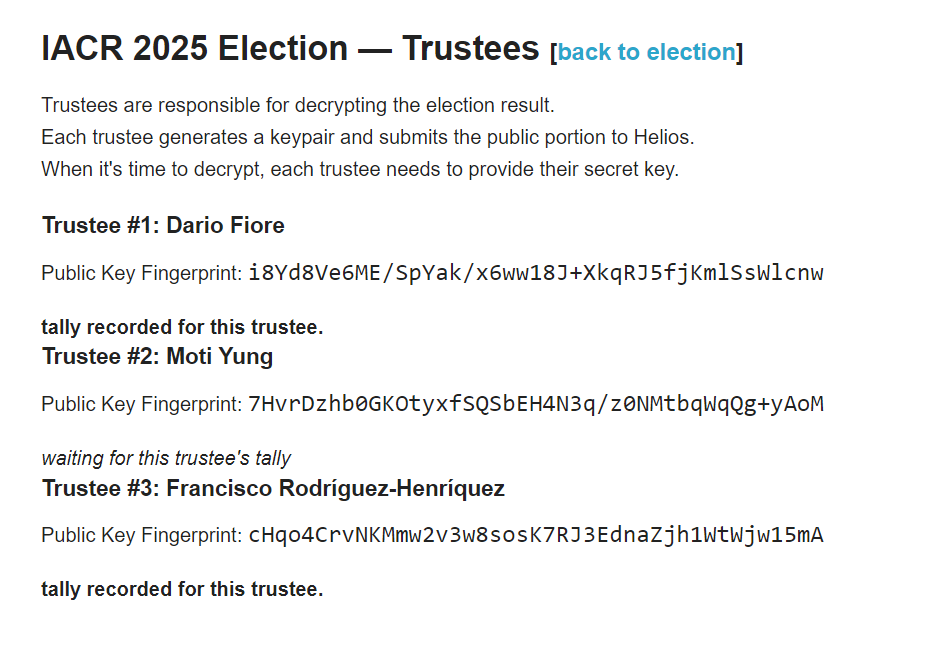

The voting period ran from October 17 to November 16. According to the association’s public election page, two trustees successfully submitted their keys following the vote’s conclusion, but Moti Yung, a cryptographer and research scientist at Google, did not.

Yung has since resigned from his trustee role for this year’s election, though the organization hasn’t explicitly confirmed whether his departure was directly connected to the incident.

Ben Adida, who created the Helios voting system, explained in a phone interview that the three keys are delivered as digital files meant to be stored on computers. In this instance, he suggested, the missing file was likely “misplaced or mistakenly deleted.”

The mishap has prompted both reflection and a touch of irony within the cryptography community. MIT cryptography professor Ronald Rivest, who praised the association’s response, noted the broader implications: “I think it’s unfortunate that this happened. Redoing the election is really costly. I think the big takeaway is you don’t want to have these kinds of errors happen in a real system.”

Adida offered a philosophical take on the situation, acknowledging that while such problems are rare in Helios deployments with the cryptology organization, the episode reveals an essential truth about even the most sophisticated security systems.

“It turns out that managing keys and managing secret keys is the hardest part of this — even among the world’s best cryptographers,” he said.

The association characterized the incident as “an honest but unfortunate human mistake” stemming from “the strict cryptographic requirements of the system itself.” Officials emphasized that the lost key cannot be recovered, and consequently, neither can the election results.

To prevent similar failures, the organization announced it will implement a more flexible approach going forward. Instead of requiring all three trustees to provide keys, they’ll adopt a “2-out-of-3 threshold mechanism” for managing private keys. The association also plans to establish clear written procedures for trustees to follow.

A new election has been scheduled to run from November 21 through December 20. Neither the association nor Yung immediately responded to requests for additional comment about the incident.

The Helios system itself is designed as a verifiable electronic voting platform that resists collusion and interference. Votes are encrypted, and individual voters can track their own ballots to ensure they were properly recorded. Despite this mishap, Adida noted that errors in the organization’s use of Helios have been exceptionally uncommon.