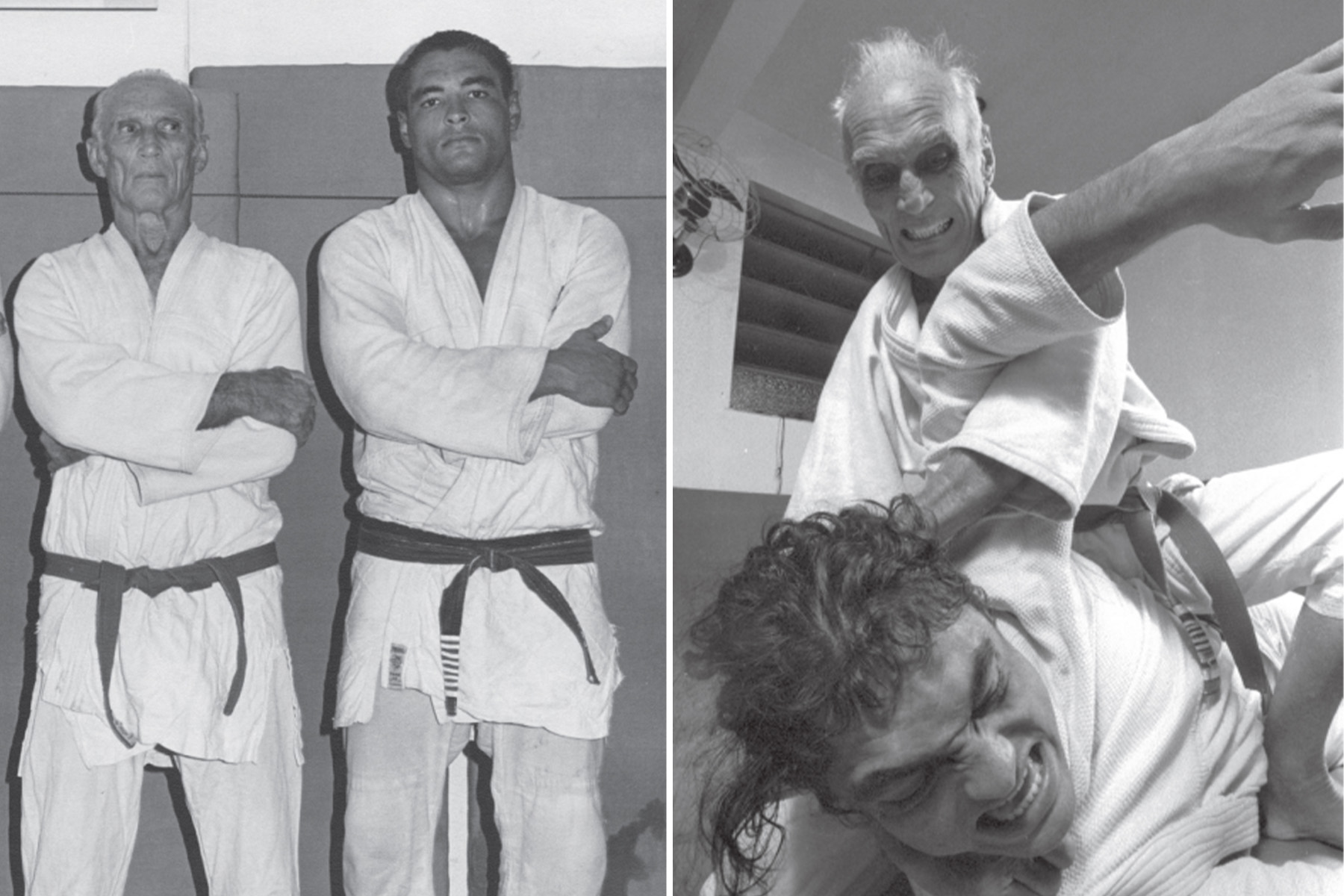

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu is often celebrated as the pinnacle of self-defense martial arts, renowned for its sophisticated ground techniques and practical application in real-world confrontations. However, the foundational narrative of its development is not merely a story of technical innovation, but also one deeply intertwined with social privilege and political connections.

The case of Helio Gracie’s near-imprisonment in Brazil reveals a stark illustration of how personal relationships and governmental influence could supersede legal consequences, even in cases of significant physical violence. In an incident recounted in a Playboy interview, Gracie describes a confrontation with Manoel Rufino dos Santos, a former luta livre champion who challenged the Gracie family’s martial reputation.

The encounter, which took place at the Tijuca Tenis Clube in Rio de Janeiro, escalated quickly. When Rufino threw a punch, Gracie responded with a takedown that resulted in severe injuries: two head fractures, a broken clavicle, and significant bleeding. Gracie himself later acknowledged the rashness of his actions, admitting that he would never repeat such a response in later years.

The legal aftermath was initially straightforward. Criminal proceedings were initiated, and Gracie was sentenced to two and a half years of detention. The Supreme Court upheld the sentence, with a telling commentary that suggested the judiciary recognized the potential broader implications of such unchecked violence: “today it was with Manoel Rufino dos Santos. Tomorrow it will be us.”

Yet, Gracie never saw the inside of a jail cell. Within two hours of the Supreme Court’s confirmation of his sentence, Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas issued a pardon. This extraordinary intervention was facilitated by Rosalina Coelho Lisboa, a student of Gracie whose brother was an ambassador and who had close ties to the president.

This episode complicates the heroic narrative often associated with Helio Gracie and the origins of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. While the martial art is celebrated for its effectiveness and philosophy of technique overcoming strength, this specific incident reveals a less romanticized reality—one where physical prowess and BJJ can get you in significant legal issue and only social connections could circumvent legal consequences.

The pardon not only saved Gracie from imprisonment but also symbolically undermined the Supreme Court’s authority. As Gracie himself recounted with a laugh, the court was “demoralized” by this presidential intervention. The personal relationship that followed—with Gracie eventually teaching the president’s son—further underscores the interconnected nature of Brazilian social and political networks during that period.

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu’s reputation as the premier martial art for self-defense must be understood within this nuanced historical context. While the technique’s effectiveness is undeniable, it’s imporant to consider that engaging in any real life incidents can land you in a world of trouble.

Helio Gracie Interview Excerpt:

PLAYBOY: Was this what led to your being placed under arrest?

HELIO: It was 66 years ago. that I was involved in my biggest trouble. A famous fighter in Brazil [a former luta livre champion] Manoel Rufino dos Santos said that he was going to show the world that we Gracies were nothing. It was at the Tijuca Tenis Clube of Rio that I gave my answer to him. I arrived and said “I came to answer the declaration that you made”. He throw a punch and I took him to the ground, with two fractures of his head, and a broken clavicle, and blood spurting out. But it was a foolish act that I did. Today I would never repeat such a thing.

23

PLAYBOY: And what happened?

HELIO: Criminal proceedings were started and I was sentenced to 2 and a half years in detention. An appeal was made to the Supreme Court [Supremo Tribunal]. My lawyer was Romero Neto. The sentence was upheld, and the court said “today it was with Manoel Rufino dos Santos. Tomorrow it will be us”.

24

PLAYBOY: How long did you stay in jail?

HELIO: I never was in jail. Two hours after the supreme court confirmed my sentence, Getúlio [the President of Brazil [Getúlio Vargas] pardoned me. One of our students, Rosalina Coelho Lisboa, whose brother was an ambassador, was very close to Getúlio and intervened, saying that it was unjust for such a youngster to be going to jail because of a street fight. He was a good person and pardoned me. The Supreme Court was demoralized [laughs]. After that I met Getúlio several times. And I taught his son, Maneco.