In the quest for eternal youth, few names shine as brightly as David Sinclair’s. The Harvard geneticist has captured the public imagination with his bold claims about reversing aging and extending human lifespan. His charismatic presence on popular podcasts and his bestselling book have catapulted him to celebrity status in the world of longevity research. But beneath the surface of Sinclair’s compelling narrative lies a troubling pattern of scientific controversy and questionable practices.

The Rise of a Longevity Guru

Sinclair’s ascent to fame began with his research on resveratrol, a compound found in red wine. He claimed that this molecule could significantly extend lifespan, a finding that garnered immense media attention and public interest. The allure of a simple, natural solution to aging was irresistible, and Sinclair quickly became the face of anti-aging science.

In 2008, riding high on the wave of enthusiasm for his work, Sinclair sold his company to pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline for a staggering $720 million. It seemed that the promise of resveratrol was about to revolutionize healthcare and usher in a new era of longevity.

The Cracks in the Foundation

However, as other scientists attempted to replicate Sinclair’s findings, cracks began to appear in the resveratrol story.

In particular, attempts to replicate his findings on resveratrol’s life-extending effects in mice have failed in other labs. Critics argue this casts doubt on the robustness of Sinclair’s conclusions. The inability to replicate results is a growing concern in many scientific fields. Replication is a cornerstone of the scientific method, allowing findings to be independently verified. When key results cannot be reproduced, it undermines confidence in the original research.

Journalist Scott Carney, in his exposé on Sinclair, argues that the Harvard professor leveraged his prestigious position and connections in the scientific community to continue publishing in top-tier journals, even as skepticism about his work grew. This raises uncomfortable questions about the integrity of the peer-review process and the potential for established scientists to manipulate the system.

Pivoting to New Promises

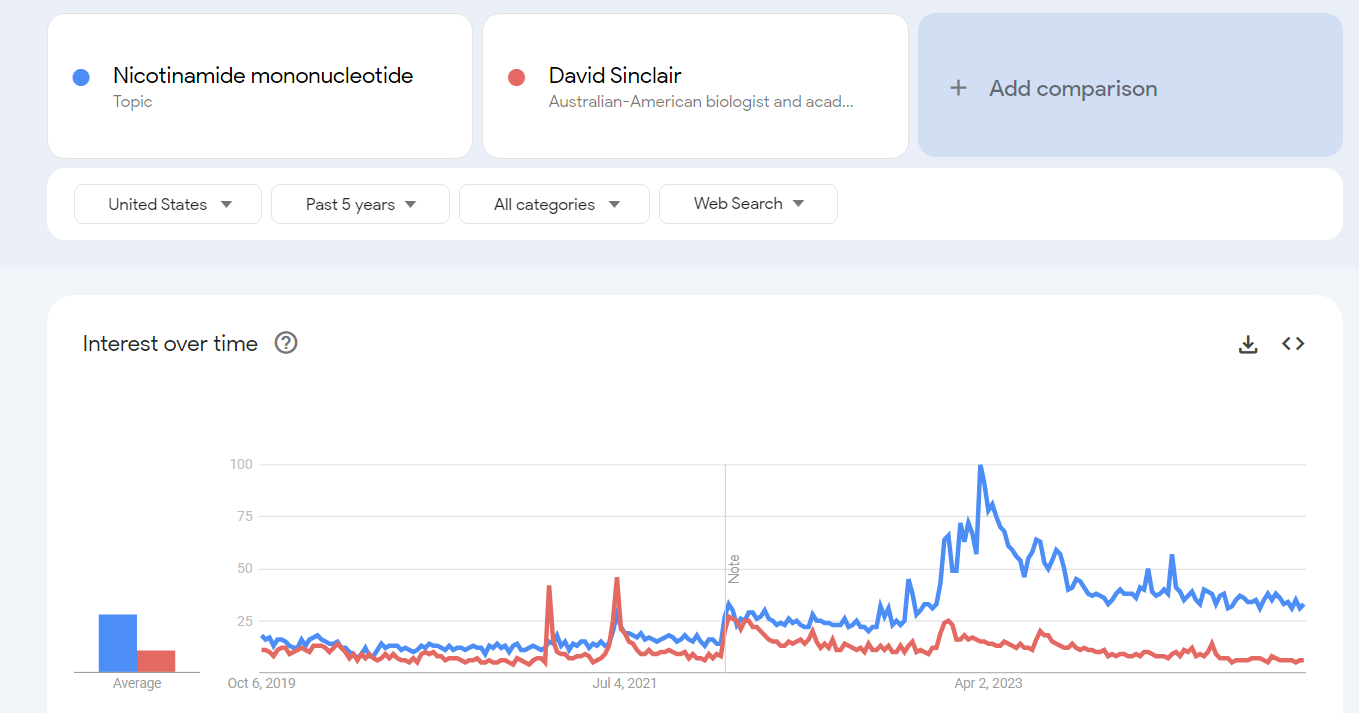

As the resveratrol claims began to unravel, Sinclair pivoted to promoting another compound: nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN). Once again, he made bold claims about its potential to extend lifespan and reverse aging. This pivot led to a boom in the NMN supplement market, with countless products flooding online stores and health food shops.

Sinclair made these claims about his personal use of NMN:

- He takes 1 gram of NMN daily, along with 1 gram of resveratrol.

- In unpublished clinical trials, taking NMN for about two weeks doubled NAD+ levels in the blood on average.

- Sinclair believes NMN is superior to other NAD+ precursors like NR (nicotinamide riboside) based on mouse studies showing greater effects.

- He recommends looking for “white, crystalline NMN” from reputable manufacturers following good manufacturing practices (GMP).

- Sinclair takes NMN in the morning, as NAD+ levels naturally rise in the morning and taking it late could disrupt circadian rhythms.

- While individual responses may vary, Sinclair reports feeling noticeably worse when he doesn’t take NMN.

- Clinical trials are ongoing to further evaluate NMN’s effects, including on muscle function in elderly patients.

However, experts including Dr. Charles Brenner and Dr. Robert Sclafani, contend that Sinclair’s work on NMN, like his resveratrol research, lacks solid scientific backing. They accuse Sinclair of repeatedly making grandiose claims that fail to stand up to scrutiny, all while profiting from the sale of supplements.

Controversial Claims and Market Manipulation

Sinclair’s promotion of NMN on platforms like Joe Rogan’s podcast helped create a massive market for these supplements. However, Carney reports that many of these products are often contaminated or fake, raising concerns about consumer safety.

In a controversial move, Sinclair reportedly used FDA regulations to corner the NMN market for his own company, further blurring the lines between his roles as a scientist and a businessman.

The Cost of Hype

The damage to Sinclair’s scientific reputation extends beyond his supplement claims. Carney highlights bizarre statements by Sinclair about “mini-brains” and reversing aging in dogs, which have further eroded his credibility in the scientific community.

Critics argue that Sinclair represents a long tradition of “immortality grifters” who exploit people’s fear of death and desire for longevity. While the pursuit of extended healthspan is a noble goal, the methods used to promote and profit from unproven interventions raise serious ethical concerns.