When Louis Theroux appeared on Chris Williamson‘s Modern Wisdom podcast to promote his Netflix manosphere documentary, the two men did not hold back in their assessments of the figures featured in the film.

Their conversation covered Andrew Tate, Myron Gaines of Fresh and Fit, HSTikkyTokky, and Justin Waller, with commentary that the subjects themselves would likely find deeply unflattering.

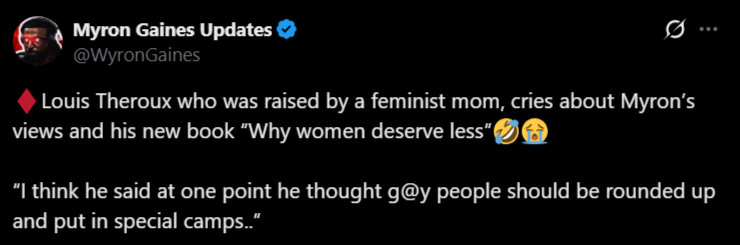

On Myron Gaines, Theroux was direct. “Myron Gaines wrote a book called Why Women Deserve Less. And his idea, his whole message is that women have been pampered and they are over-entitled.” He also noted that Gaines’ worldview appeared to be shaped by a narrow social circle, adding, “I think a lot of it seems to be based on his interactions with cam girls and OnlyFans models.”

Theroux went further when describing some of Gaines’ more provocative statements, noting, “I think he said at one point he thought gay people should be rounded up and put in special camps.” He acknowledged some uncertainty about whether the comments were sincere, observing that Gaines would sometimes walk statements back: “He’ll be like, ‘Oh, well, I’m not literally saying what I mean,’ and they start pausing it and making it sound more acceptable.”

On Andrew Tate, Theroux described one of his early monetization strategies in stark terms: “One of his first products was the so-called p*mp and PhD p*mp and ho*s degree. He’s tried to walk that back now, but obviously the whole paper trail is there online, describing how you have to get a girlfriend and have s*x with her and then she’ll fall in love with you and then you introduce her to Camming and then you take her money.”

Theroux also addressed Tate’s upbringing as context for his worldview: “The chaos in Tate’s household growing up, he talked a lot about how his dad would come by and beat him up. ‘One good a*s whipping’ is one of his quotes. The idea that there’s massive educational value in being beaten up by your dad is kind of extraordinary.”

Theroux framed the business model bluntly: “They’re in this continuous feedback loop of being rewarded for some things and not others. You’re performing masculinity. You’re not embodying it.”

Williamson agreed, saying: “You’re reverse engineering what would a man who is this sort of a man do, and rather than make myself into that man, I’ll just pantomime his actions.”

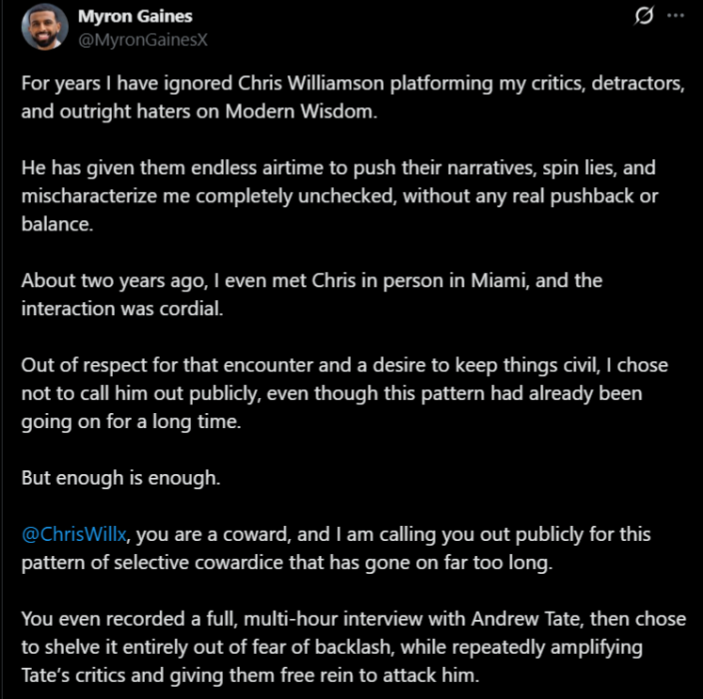

Following the interview, Fresh and Fit host Myron Gaines responded publicly, directing his criticism not only at Louis Theroux but also at Modern Wisdom host Chris Williamson for giving the journalist a platform.

In a lengthy post on X, Gaines accused Williamson of repeatedly allowing critics to attack him without offering him the opportunity to respond.

“For years I have ignored Chris Williamson platforming my critics, detractors, and outright h*ters on Modern Wisdom,” Gaines wrote. “He has given them endless airtime to push their narratives, spin lies, and mischaracterize me completely unchecked, without any real pushback or balance.”

Gaines also revealed that he had previously met Williamson in person and claimed the interaction was cordial. According to him, that meeting was the reason he initially chose not to publicly criticize the podcast host.

“About two years ago, I even met Chris in person in Miami, and the interaction was cordial,” Gaines said. “Out of respect for that encounter and a desire to keep things civil, I chose not to call him out publicly.”

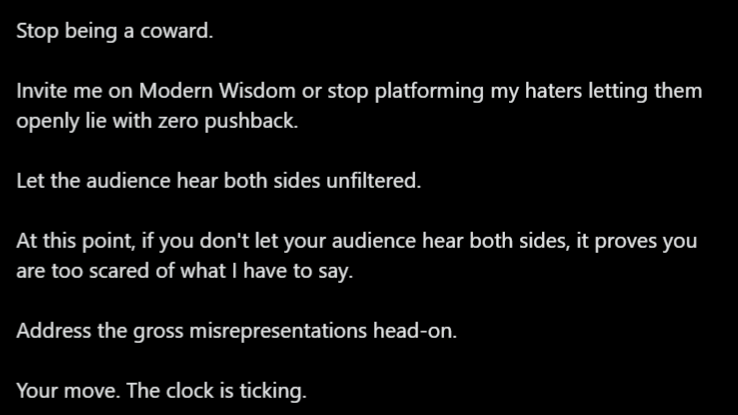

However, Gaines said the interview with Theroux crossed a line. In the same thread, he directly called out Williamson and demanded the opportunity to present his side of the story.

“Stop being a coward. Invite me on Modern Wisdom or stop platforming my h*ters letting them openly lie with zero pushback,” Gaines wrote. “Let the audience hear both sides unfiltered.”

He also claimed that Williamson had previously recorded an interview with Andrew Tate but chose not to release it. “You even recorded a full, multi-hour interview with Andrew Tate, then chose to shelve it entirely out of fear of backlash,” Gaines alleged.

Gaines was similarly critical of Theroux’s documentary itself, accusing the filmmaker of selectively editing material to push a particular narrative.

“And now Louis Theroux, disingenuous as ever in his so-called journalism, has released his manosphere documentary,” Gaines wrote. “He selectively edited and framed the footage to push a clear agenda, conveniently omitting key context and moments that would have told the full, unfiltered story.”

According to Gaines, he recorded his own interactions with Theroux and suggested he may release them publicly.

“Fully expecting this, I recorded all my interactions with Louis Theroux and his team. Tonight, I am exposing exactly what he was too scared to include,” he wrote.

Gaines concluded by reiterating his challenge to Williamson, arguing that audiences should hear both perspectives.